When to Stop Attacking Your Attacker

When you’re thrust into a situation where you’re forced to defend yourself, adrenaline kicks in, and your focus narrows. Your primary objective becomes survival.

But knowing when to stop attacking your attacker is just as important as knowing how to defend yourself.

The moment to cease your counterattack is when your assailant is no longer capable of posing a threat – when they’re physically unable to continue their assault.

The Thin Line Between Defense and Excessive Force

In any self-defense scenario, the law typically allows you to use reasonable force to protect yourself. But here’s the rub – what constitutes “reasonable” can be a grey area, often defined by the heat of the moment. As an operative, you need to keep your cool and understand the threshold where defense turns into excessive force. Crossing that line can lead to serious legal consequences or escalate a situation unnecessarily.

When you’re under attack, your goal is simple: neutralize the threat. This doesn’t mean you continue attacking until your assailant is unconscious or worse. It means you stop as soon as they are no longer a threat to you. In most cases, this means they’ve either fled, are immobilized, or are visibly incapacitated.

Recognizing When the Threat is Over

So, how do you know when to stop? The moment to disengage is when the attacker is no longer capable of harming you. This could be when they’re on the ground, unable to get up, or when they’ve clearly decided to back off. A good rule of thumb is if they’re not in a position to continue their attack, you stop yours.

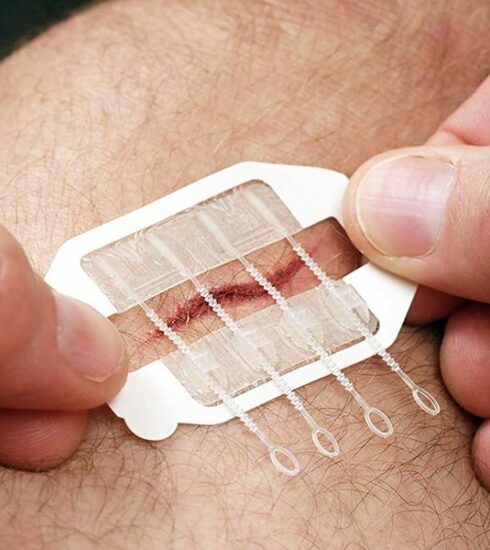

Physical Incapacitation

If your attacker is on the ground, unable to stand, or holding an injury that clearly prevents further aggression, it’s time to stop. This might mean they’ve sustained a blow to the head, a broken limb, or some other incapacitating injury. They’re down and out; there’s no need to add more damage.

Submission or Retreat

If the assailant starts begging for mercy, or even better, starts retreating, you’ve achieved your goal. They’re no longer in an offensive posture, so continuing to attack only shifts you from defender to aggressor.

Weapon Neutralization

If the attacker was armed and you’ve disarmed them, you’ve effectively neutralized the threat. Without a weapon, unless they’re still physically capable and intent on continuing the attack, you should stop.

Walking Away: The Smart Move

Once the threat is neutralized, the best move is to disengage and walk away. Staying in the heat of the moment can lead to more trouble, either from the attacker regaining the upper hand or from authorities misinterpreting the situation. Leaving the scene once the danger has passed is often the wisest course of action. It shows that you were acting in self-defense, not out of a desire to harm.

Walking away also gives you the opportunity to assess your surroundings and ensure there’s no further danger, including from potential accomplices or bystanders who might misinterpret your actions.

Lethal Action

The Mindset of Control

The real skill here is control. In any self-defense situation, it’s crucial to maintain control – not just of your body, but of your emotions and your actions. Losing control can turn a self-defense situation into something far more dangerous, both legally and physically.

As operatives, we’re trained to use only the force necessary to neutralize a threat. The same principle applies in civilian life. Self-defense isn’t about revenge or punishment; it’s about survival. Once you’ve ensured your safety by incapacitating your attacker, the fight is over. Anything beyond that is unnecessary and could land you in serious trouble.

In the end, the best defense is one where you protect yourself without crossing the line into unnecessary aggression. Neutralize the threat, walk away, and live to fight another day.

[INTEL : Elevator Self-Defense Guide]

[OPTICS : London, England]